How One Owl’s Fate Led to One of My Favorite Pieces of Jewelry

At some point during the pandemic I went from being a casual bird watcher to a full-on birder. If birds were cars, I went from driving around on nice days to going full throttle on a professional track going through tires. If birds were a meal, I went from adding a pinch of this, and little bit of that to cooking over a 5 burner stove imported from France using only farm to table ingredients for my 5 course meals. You get the drift. What is it about birding that is so satisfying, or why do I continue to do it? Maybe it’s part of the mystery that is part of the draw. Never knowing what to expect. Always curious for more. Nearly every time I find myself walking around outside usually with a camera in tow, I always wonder thoughts similar to these. I developed a passion for birding that went far beyond a pair of binoculars. I dove into scientific names, migration patterns and even started that crazy endeavor of rising before the sun to catch the dawn chorus and enjoy the fastidious activity of birds in the wee hours just before sun up. While I didn’t know it at the time, I was practicing gökotta, the Swedish practice of rising early to hear the morning bird song. My nightstand is like an avian library with titles such as “What the Robin Knows” and “The Bird Way”. My license plate frame tells it how it is: “Bird Nerd”. Thankfully, the nature of my home lends itself well to attracting birds to my yard, so I mostly don’t have to travel far to see them. Before I crossed over from bird watcher to full on birder somewhere along the line during the COVID-19 pandemic, a curious thing happened right in our front yard. It was a bright, cold January day in 2019. Three years to the day from the publishing of this post. My family was out in the yard (as we often are) and my husband spotted a shiny trinket in the grass. Not much bigger than a pea, but in the low sun, it was easy to spot in the short brown grass. It was a band. A bird band. There was a leg, and a band still attached to it, a pile of bones, with a tiny twinkle.

An Owl Pellet

Bird Band

Eastern Screech Owl*

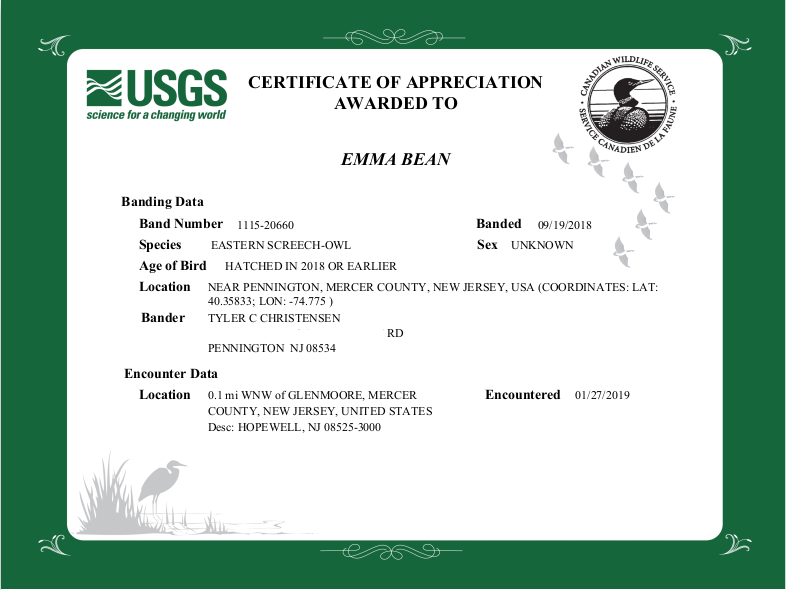

This is the certificate we received.The North American Bird Banding Program

“Bird banding is important for studying the movement, survival and behavior of birds. About 60 million birds representing hundreds of species have been banded in North America since 1904. About 4 million bands have been recovered and reported. Data from banded birds are used in monitoring populations, setting hunting regulations, restoring endangered species, studying effects of environmental contaminants, and addressing such issues as Avian Influenza, bird hazards at airports, and crop depredations. Results from banding studies support national and international bird conservation programs such as Partners in Flight, the North American Waterfowl Management Plan, and Wetlands for the Americas.”

So, where is the band now? Also on my nightstand, and it is one of the best accessories I own. It’s a necklace. While the fate of one owl was one of our best bird stories yet. “Thank you owl. I’ll wear that now.”

So, where is the band now? Also on my nightstand, and it is one of the best accessories I own. It’s a necklace. While the fate of one owl was one of our best bird stories yet. “Thank you owl. I’ll wear that now.”

*I took this photograph of an Eastern Screech Owl while with Wild Bird Research Group‘s (WBRG) Saw-Whet Owl banding program in November 2021.

WBRG studies the migration and winter ecology of eastern North America’s smallest owl, the Northern Saw-whet Owl. WBRG staff capture and band Saw-whet Owls at multiple sites during the fall migration, and participate in a continent-wide network of owl researchers studying large-scale Saw-whet biology. During the winter, WBRG fits Saw-whets with temporary radio transmitters to track their movements and identify critical roosting habitat characteristics.Occasionally, they also band Screech Owls during the Saw-Whet owl banding program. They get a little bling too, and are documented with information gained from its wing length and its weight. The owls are then released. You can adopt one of these adorable little owls. They are the smallest owl in eastern North America. If you are interested in adoption, find out more about it here.

Saw-Whet Owl

Chickadee with a bird band

One response

[…] further reading on bird banding and why it is done on songbirds, owls, and raptors, refer to another one of my posts “Owl Wear That […]